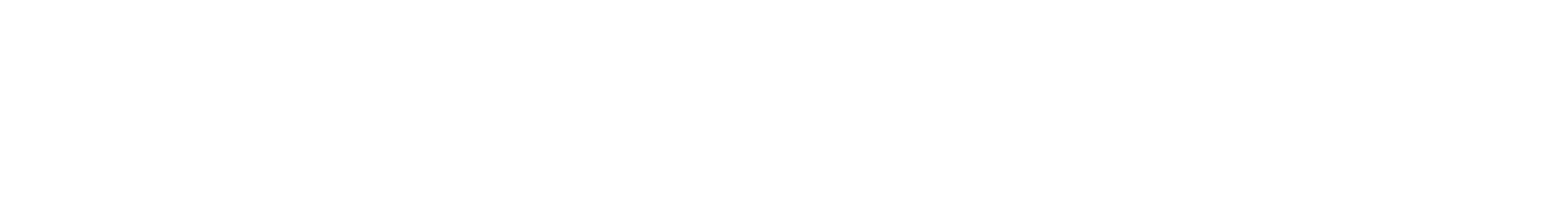

In its glory days, the eighth floor auditorium of Dayton’s department store in downtown Minneapolis buzzed with crowds during its yearly holiday show. For longtime Twin Cities residents, the images that come to mind likely include elaborate themed displays and excruciatingly long lines. For one show with the theme “Dickens’ London Towne”, Dayton’s Senior Executive, Joseph R. Wright, secured a pianoforte built in Berlin in 1830 by Heinrich Christian Kisting & Son in Berlin. Following the close of the holiday show, Wright donated the instrument to Schubert Club in 1972. Before the organization moved into its current and more spacious home in Landmark Center in 1978, this gem of a piano was stored in Executive Director Bruce Carlson’s office at the Saint Paul Arts & Science Center. It seems likely that acquiring this storied pianoforte sparked the idea of building a Schubert Club historical keyboard collection.

The Kisting’s star-studded backstory set a high bar for the burgeoning collection. It was originally purchased for Adolf von Menzel, a German realist painter known for the lively salons–or parties–he hosted for local artists and aristocrats in his Berlin apartment. Often in attendance at these events were familiar musical names like Clara and Robert Schumann, Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn, and Johannes Brahms, all of whom likely graced its keys. The Kisting acquisition primed the pump for a string of successive donations of historical keyboards, some with equally strong connections to famous composers. One of special note is an 1844 upright piano by Sébastien Érard, inside of which is found a humble inscription left by Franz Liszt while rehearsing on tour in Lyon, France, in 1844: “I confess to having played wrong notes and scribbled wretched music on this charming instrument.” It wasn’t until 1980 that Schubert Club had finally amassed a collection sizable enough to open its Keyboard Instrument Museum in the basement of Landmark Center.

It makes sense that the keyboard collection enjoyed such robust growth at a time when there was heightened interest among classical musicians in historically informed performance. Drawing inspiration from figures like Noah Greenberg and Christopher Hogwood in the 1950s and 60s, as well as earlier proponents like Arnold Dolmetsch, this movement advocated for deeper exploration of the music by utilizing the authentic instruments and techniques of the era when it was composed. At a time when electrified genres like funk and rock and roll were on the rise, and when classical virtuosos felt pressed to dazzle wider audiences, the expansion of Schubert Club’s keyboard collection symbolized a desire to reconnect with the roots of classical music.

Despite its many gorgeous instruments, the museum’s focus has never been interior design; rather, every keyboard is treated as a living piece of music history. What we know today as the piano was invented in 1700 by Italian harpsichord maker Bartolomeo Cristofori, whose ingenious hammer action design allowed the performer to play both softly and loudly. Previously, harpsichords and clavichords could play only at one volume level. Fittingly, he dubbed his creation a gravicembalo col piano e forte (Italian: “harpsichord with soft and loud”), which was eventually shortened to pianoforte, and then again to piano.

1997 replica of 1726 pianoforte by Bartolomeo Cristofori

Schubert Club’s Keyboard Journey gallery features a 1997 replica of a 1726 Cristofori pianoforte as well as fifteen other pianos that look and sound vastly different from one another. For example, whereas the 1795 grand piano by English manufacturer John Broadwood & Sons features foot pedals, the 1768 square pianoforte built by Johannes Zumpe in the same country only 30 years prior boasts a set of awkward yet functional hand levers. Building upon Cristofori’s original prototype, each instrument in the collection represents a chapter in the piano’s 300-year history of experimentation, modification, and improvement.

The age of Schubert Club’s keyboards has not prevented some of them from being featured in public performances throughout the years. Of the many notable artists who have performed on the collection’s instruments, two of the biggest names are pianists Jörg Demus in 1982 and Peter Serkin in 1983. More recently, a reproduction of an 1824 pianoforte by Conrad Graf was featured in the joint performance of mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter and keyboardist Kristian Bezuidenhout in November 2022 in Schubert Club’s International Artist Series. The public was also treated to daily demonstrations of the collection by museum guides throughout the 1980s. While these presentations have since been phased out to preserve the instruments’ structural integrity, visitors to today’s Keyboard Journey gallery can still hear them come to life through recordings made on the instruments displayed. Those looking for a more hands-on experience will enjoy The Music Makers Zone, a gallery created in the spring of 2021 where visitors can play instruments from around the world, including various keyboards and percussion.

After 43 years of expanding and evolving, the Schubert Club Music Museum has held to its belief that music is not a luxury, but rather a deeply human process. In the museum’s current iteration, there are more opportunities than ever for visitors to discover their own connection to music, completely free of charge. To plan your visit to the museum, visit schubert.org/museum. You can also view Schubert Club’s collection of rare musical instruments online! To access the database, visit schubert.org/collection.

Sources:

Kenyon, Nicholas. “Early Music Is Enjoying Its Moment.” The New York Times, 4 Mar. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/03/06/arts/music/06early.html.

Powers, Wendy. “The Piano: The Pianofortes of Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731).” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Oct. 2003, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cris/hd_cris.htm#:~:text=The%20pianoforte%2C%20more%20commonly%20called,anything%20an%20orchestra%20can%20play.

The Schubert Club 125th Anniversary: Musings and Memories, edited by Sharon Carlson & Holly Windle, Schubert Club, Saint Paul, 2007, Print.

The Schubert Club Museum, edited by Bruce Carlson, Schubert Club, Saint Paul, 1991. Print.